The Commonsverse is the loosely connected world of different types of commons, which can be seen as a federated pluriverse of commons. Here are some of the more active zones of the Commonsverse today:

Relocalized Food (pp. 41-42 and pp. 46-50)

To reduce their dependence on Big Agriculture and enhance their resilience, many local communities are embracing community supported agriculture, community land trusts, agroecology, the principles of Slow Food, urban farming, and other types of relocalized food.

Local Infrastructures for Shared Benefit (pp. 39-40 and p. 60)

The Catalonian WiFi system known as Guifi.net, and Solar Commons projects in Minnesota that produce electricity, show how commoners can go beyond corporate and municipal systems, introducing commons-based infrastructures that can benefit everyone.

Community Land Trusts (pp. 41-42)

By removing land from speculative real estate markets, community land trusts lower the overhead costs for farming, small enterprises, homeowners, and renters. CLTs provide an effective organizational tool for community stability and against gentrification and industrial agriculture.

Subsistence Commons (pp. 47-49 and pp. 55-56)

An estimated two billion people in poor, rural regions depend on the commoning of forests, fisheries, irrigation water, and other natural systems for their daily life. Often denigrated as premodern, these commons nonetheless tend to be more eco-friendly and fair-minded than markets.

Convivial Conservation (pp. 44-45)

Rather than cordon off nature as “wilderness” or use capitalist markets to make nature earn its keep, some conservationists see greater promise in what they call “convivial conversation” – responsible (nonmarket) stewardship of land supported by a “conservation basic income.”

Racial Justice through Commoning (pp. 86-91)

In the face of racial violence and exploitation, a distinctive African-American tradition of commoning has helped people acquire and preserve land through land trusts, build food sovereignty through cooperatives, and in other ways create a more secure future with dignity.

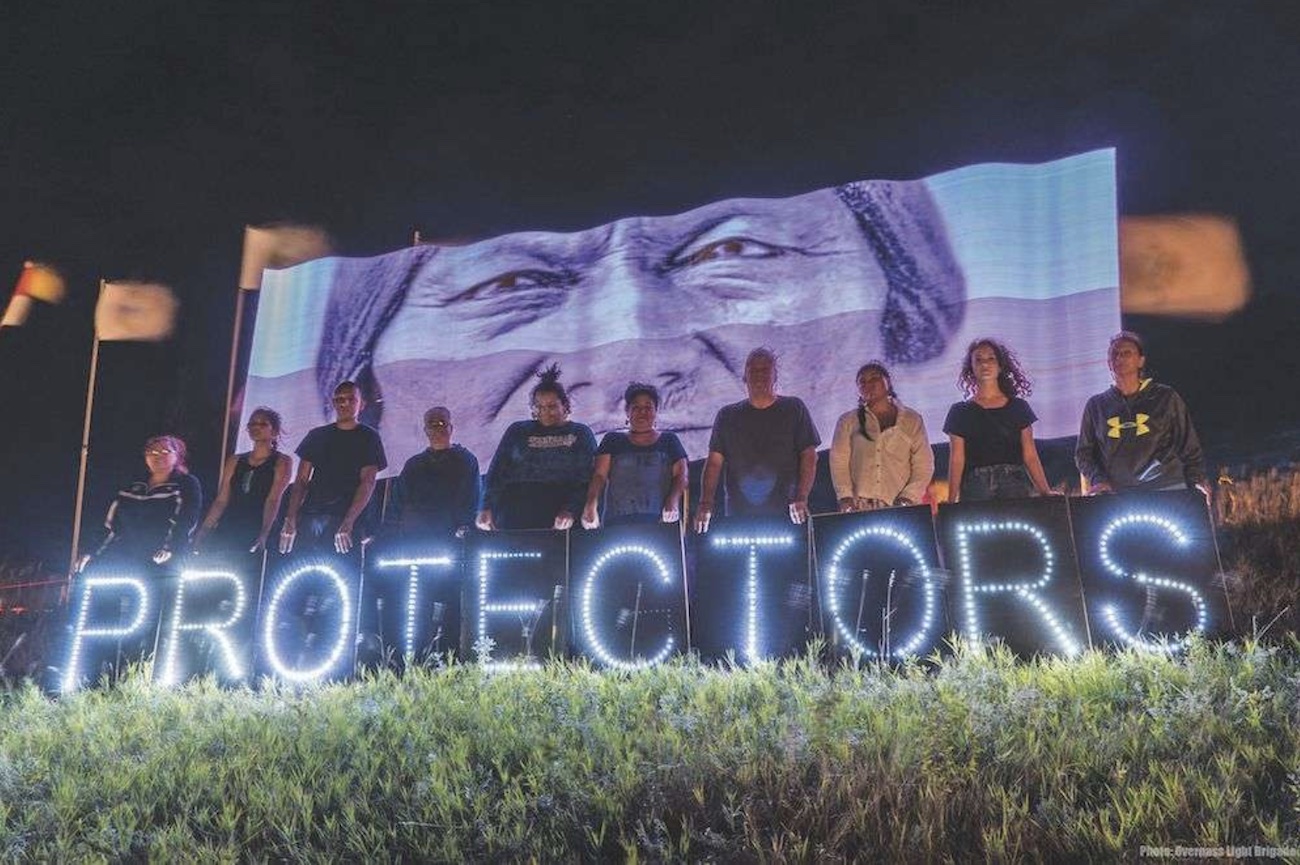

Water Stewardship (pp. 51-54)

While water for drinking and crops is often scarce, commoning can responsibly steward it in fair, sustainable ways. Examples abound: traditional acequias in New Mexico, the work of Water Protectors at Standing Rock, the subak irrigation systems of Bali, and the Milwaukee Water Commons.

Community Charters (p. 39)

Community charters are written declarations that neighborhoods, towns, or entire cities create to assert a positive, long-term vision of the people, especially to challenge local government and corporations that are ignoring the public, such as through hydrofracking.

Gift Economies (p. 22)

Contrary to standard economic theory, giving away one’s time or property can be a powerful source of value, as seen in gift economies of artists, scholars, Indigenous peoples, and open-source software programmers. Gifts elicit and sustain collaboration, sociability, ethical behavior, and trust.

Life Itself as a Commons (pp. 25-29)

Many biologists now argue that life itself can only develop through complex, symbiotic relationships with other living organisms. An individual focus is too limiting because life arises through a rich “symphony of relationships” and interdependencies – which is the very point of commoning.

Care Work (pp. 81-85)

While markets often attempt to “buy care” by paying people for their labor, human care and commitment ultimately answer to a different coin – authentic affection, trust, reciprocal commitment. Commoning is often indispensable for eliciting these qualities of care.

Alternative Currencies (pp. 79-80)

Around the world, more than 6,000 alternative currencies help communities capture and recirculate value created within their territory while preventing the outside economy from siphoning it away. This enhances the economic resilience, culture, and identity of a region.

Timebanking (pp. 78-79)

Where money is scarce, timebanking is used as a service-barter system for people to exchange an hour of services given – lawn-mowing, babysitting, errands – for an hour of services needed. A worldwide phenomenon, timebanking helps people without money meet needs and build social connection.

Open access scholarly journals (pp. 74-75)

More than 16,000 academic and scientific journals, such as the Public Library of Science journals, make research free to read, copy, and share in perpetuity, overcoming exorbitant subscription fees and copyright paywalls. OA journals help equalize access to knowledge.

Licenses for Sharing Knowledge (pp. 68-69)

Businesses make money on software, music, video, and texts by claiming absolute and exclusive control through copyrights. To fight the criminalization of sharing, commoners invented Creative Commons and other licenses that have spawned vast repositories of legally shareable content.

Peer Production (pp. 63-65)

The rise of the Internet has shown the remarkable power of networked collaboration, a.k.a. peer production. It is now a driving force in open source software, Wikipedia, collaborative archives, open science, cosmolocal production, and many other forms of value-creation.

Platform cooperatives (pp. 94-95)

Because tech companies have captured and monetized much of the value generated by online social networks (misleadingly called the “sharing economy”), commoners are devising peer-owned “platform cooperatives” to empower users while thwarting online monopolies and data surveillance.

Open Educational Resources (pp. 75-76)

By conceiving education as social process of sharing and building on existing knowledge, a movement dedicated to Open Educational Resources is creating high-quality textbooks, curricula, databases, and other materials that are shareable and affordable.

Crowdfunding and Crowdequity (pp. 77-78)

While much crowdfunding simply providers free seed-capital for startup companies, with no shared equity or peer governance, many crowdfunding platforms such as the Madrid-based Goteo actively use this digital tool to help commoners finance, build, and own their own commons projects.

Cooperatives (pp. 92-95)

Cooperatives have a long history of meeting people’s needs in fair-minded, participatory ways, rejecting the exploitative practices of many conventional businesses. With local roots and democratic processes, coops can also be a powerful force for reducing inequality and over-consumption.

Digital Infrastructures (pp. 66-67)

Rather than rely on private, proprietary telecommunications and software infrastructures, commoners are extending the idea of the Internet’s TCP/IP protocols and the Web’s HTML standards by building infrastructures for online deliberation, cloud services, and peer-to-peer networking.

Arts and Culture (pp. 97-102)

While much art and culture are now crafted to sell as commodities in the marketplace, many artists are embracing commons and gift economies as important vehicles for nourishing their creative powers. Why? They help sustain honest, deeply human relationships with peers and audiences.

Co-creating Cities (pp. 59-62)

Because the design and governance of cities too often reflects the priorities of investors, political cronies, and the affluent, a new movement seeks to empower urban commoners to directly steward buildings and public spaces, allocate budgets, and bring the commoning ethic to public administration.

System-Change Movements (pp. 106-109)

Many movements seeking system-change do not necessarily identify as commoners or share the same agenda. But each – Degrowth, the Solidarity Economy, cooperatives, and many others – believes in the generative power of cooperation, peer governance, and living systems.

Universal Property (p. 72)

Market capitalism is structurally inclined to destroy natural systems for private gain and to concentrate wealth in the hands of a few. But if we invented new forms of “universal property” for our co-inherited wealth – the atmosphere, water, the financial system, etc. -- new types of independent trusts and social wealth funds could protect our shared wealth while generating new revenue streams to reduce inequality.

Leading Websites Focused on Commoning

Bollier.org (US): bollier.org

Commons.fi (Finland): commons.fi

Commons Institut (Germany): commons-institut.org

Commons Network (Netherlands & Europe): commonsnetwork.org

Commons Strategies Group (international): commonsstrategies.org

Commons Transition (international): commonstransition.org

Commonverse: Commonsverse.commoning.wiki

Foundation for Ecological Security (India): fes.org.in

Guerrilla Media Collective (Spain): guerrillamedia.coop

International Association for the Study of the Commons: iasc-commons.org

International Journal of the Commons: thecommonsjournal.org

Indigo Project (Flanders): theindigoproject.be

Institute for Political Ecology (Croatia): ipe.hr/en

Institutions for Collective Action: collective-action.info

Journal of Peer Production: peerproduction.net

P2P Foundation: p2pfoundation.net

Pillku (Latin America): pillku.org

Remix the Commons (French and English): remixthecommons.org

Shareable Magazine (US): shareable.net

Stir to Action (U.K.): stirtoaction.com

Think Commons (Spain): thinkcommons.org/en